Loretta Creech

|

My name is Loretta Creech. I am the author of the book "No Tears For Ernest Creech, a forgotten man in the great society."

The book is available on Amazon and other web sites and can be read into on amazon. This is a true story about the life and death of a coal miner and was a big story in 1965 when he was shot down in cold blood by a group of pickets at the leatherwood mines in leslie county. My e-mail address is [email protected]and my phone # is 859-273-6277. I graduated from M.C. Napier high school in 1967 and went on to Alice Lloyd College in Pippa Passes Ky.on a scolarship in music. After Alice Lloyd I went on to Eastern KentuckyUniversity to major in business. I actually wrote the book, or made notes to myself while a student at Alice Lloyd after talking to Robert Kennedy who inspired me to put my story down in writing but it was not until 2006, after retiring from Toyota Motor Manufacturing, that I put my notes together in the form of a book and summited it for publication. The book was written from the thoughts of a 17 year old girl who was still grieving from the death of her father. The language and dialect was written in that style. The book can be purchased on any web site. |

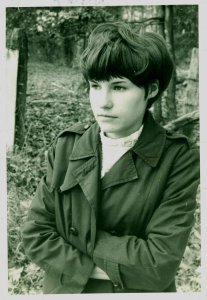

I, Loretta, at age sixteen.

|

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Chapter 1

Mr. Humes’s Visit

|

In November of 1965 an article was written by Mr. Ted Humes for the “HUMAN EVENTS” magazine out of Washington D.C... It was titled “NO TEARS FOR ERNEST CREECH” with a sub-heading, “The ‘great society’ claims to be helping the people of Appalachia, but it does nothing to protect the individual working man from union violence.” In this article he wrote, “On that grey morning as Creech’s pickup truck approached the entrance to Leatherwood No.1, a piece of slate thrown at his truck broke the rear window, just missing him and sending slivers of glass throughout the cab. As one raised in an atmosphere of roving pickets and minefield violence, Creech continued on to work and put in a full day down in the shaft. At noontime he purchased a rifle, fearing the worst. As he left the mine site at 4 p.m. he was met by a small army of parked cars near the entrance, gun barrels sticking out of many of them. He drove on, carrying with him fellow workers Carl and Bentley Boggs until they were blocked ahead by another car. Creech got out of his truck and tried to talk his way through. Whether or not he succeeded will never be known, because the moment he returned to his truck and sat down. A 30.6 slug ripped through and pierced his heart through the left shoulder blade. Ernest Creech, 38 years old, was dead almost instantly; Gladys Creech became a widow and nine children lost a father; three weeks later a 10th child was born, Ernest Jr.” I have often wondered how Mr. Humes got so much information from the short visit he made to our house in late September of 1965. He came walking up Crawford road, over the bridge into our yard and up the steps to our front porch just about the time us children were getting home from school. He had been well shaven, dressed in a handsome black suit and his crow black hair had been combed back slick and well placed. At the time we felt he was just another “city slicker” who had come to our house to get our sad story. We had seen a lot of these people since daddy’s death; people from the United Mine Workers, the Southern Labor Union and strangers from newspapers. Mr. Humes sat down in one of our hard bottomed chairs on the front porch, took out his thick black book, his shiny silver pen and started writing, asking mommy questions about daddy. Mr. Humes described mommy in his article the day he came to visit. “She was ironing on the front porch of her frame and concrete block home situated along a dry creek about five miles from Hazard. The wooden rail was large enough to hold the pile of finished ironing. At the moment her prime concern was a leaking roof and she had been trying for two weeks to find somebody to fix it. The dampness had given her children sore throats and they had been missing school. Finally Charlie Campbell, a retired miner, now working on a county road improvement project, came over and started nailing tar paper over the kitchen.” I was sitting on the top of the steps, arms locked around my knees, listening to their every word. Mr. Humes quoted the words very well that came out of Mommy’s mouth that day. “He just lived for his family, she said, fighting to hold back the tears. The last time he went out on strike we all but starved to death--he cried and told me he couldn’t hold up with the union unless they fed his kids. He was good to his kids, and took the boys with him everywhere he went. When Ernest wasn’t working at the mines, he would take his truck and go out hunting junk to make an extra dollar-he did a little hunting and fishing. He had an old outboard motor, but usually rented a boat down at buckhorn dam....he wanted nothing more than to take care of his family.” Mr. Humes asked mommy to gather all her children on the steps going up to the front porch so he could take our picture. He described the way he saw us that day in his article. “Terry is 2, blond, barefooted and towheaded; he was playing with a plastic doll on the wooden steps leading to the porch. His brother Larry is 4 and wears a faded “Flintstone” sweatshirt and was cutting an apple which he had picked up in the backyard. Ernest Jr. is four months old now; he was born 13 days after his father’s death. He was sleeping serenely on his mother’s bed, a beautiful bouncy lad with curly hair; soon he began to stir and Gladys Creech put away her ironing and picked him up to nurse him. The Creech girls are all bright and alert children; their grades are uniformly good, and they are well-disciplined, the product of good parental influence.” Mr. Humes took our picture, thanked mommy, and left. As far as we were concerned that was all there was to his visit, but in late November letters and packages started coming to our house. The mail man told mommy there were too many packages for him to deliver so she needed to go to the Hazard to the Post Office and get the rest. The next day she got her daddy to take her and they came back with a car filled with packages containing clothes, shoes, canned food and a bunch of other things. From a feed sack mommy poured stacks of envelops containing checks and money. Grandpa said the things had come from California and Washington D.C, and some of the things had even come from the movie star, Lucille Ball. She had read Mr. Hume’s article he had written about us in” HUMAN EVENTS” Magazine and sent these things to help us out. I wondered about these “furriners”. They knew nothing of our life. Why did they care about us? Had they ever been up here in these mountains? Did they even know where or who we were? Mr. Humes wrote, “Words are poor things at the best of times: to attempt to describe the murder of Ernest Creech they are wholly inadequate. For these are the woods and the meadows that he knew and the scenes that he loved so well. He was three when he came to Eastern Kentucky from Detroit. Except for service in France with the army in World War II, this was his country.” Mr. Humes had been referring to the little community on Crawford Mountain where we had lived. The road, coming up Crawford Mountain from Hazard, the county seat of Perry County, had gone right past our house. This road, which had been surrounded on both sides by the mountains, weaved out like a spider web leading to Bonnyman, Blue diamond, Typo, Grapevine, and Buckhorn. There were also several hollows that came off these roads and went back inside the mountains. They didn’t have any names. We just called them hollows. Our lives had been typical of most children growing up in and around Hazard in the sixties. Your daddy worked in the coal mines, you went to school, did your chores, helped with your younger brothers and sisters, and wondered where your next meal was coming from. We were poorer than most but yet, not as poor as some. There were times, in the winter, that food became scarce but in the summer the earth provided most of what we needed. Mr. Humes gave a description of what he saw at our house the day he came to visit. “Like most of the old company homes of this region, the Creech property is somewhat barren and run-down by modern standards. There are three bedrooms, a parlor and a kitchen; the furniture is of poor quality, walls are bare, un-plastered and the light switches hang loosely from the wall. There is a noticeable lack of cupboard space and the girls’ dresses hang on open racks. The Creeches managed to secure a fairly good refrigerator and range and their only other luxury item is a TV set they bought about three years ago.” This had been the way we had lived. I knew we were poor and thought we would probably always be poor, but I did have dreams. I dreamed of things I knew I would probably never have. They weren’t big dreams, just dreams of having store-bought dresses or fancy shoes. Our school dresses had been made from the feed sacks mommy and daddy had got flour and meal from. Mommy was good with her old pedal sewing machine but I still wished I could have store bought clothes. I tried to act proud of my princess style dresses, as mommy called them, but some of the kids made fun of my sisters and me. Shoes were sometimes scarce; mostly we didn’t wear them in the summer. |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~